DESCRIPTION OF EXHIBIT

Days of Distraction

Alexandra Chang

In her compelling debut novel, "Days of Distraction," Alexandra Chang delves into the complex intersection of race and relationship. Despite a history of anti-immigrant sentiment directed at Asian Americans, contemporary trends reveal high intermarriage rates within this community.1 This shift in societal attitudes prompts a closer examination of the racial and cultural implications of such partnerships. Therefore, my digital exhibit aims to investigate the dynamics of interracial relationships, with a primary focus on East Asian women with White partners, in the broader context of the marginalization of Asian Americans.

[1]

Book Summary

Author Alexandra Chang promoting Days of Distraction [2]

“A wry, tender portrait of a young woman—finally free to decide her own path, but unsure if she knows herself well enough to choose wisely—from a captivating new literary voice.” 3

Days of Distraction follows the journey of an unnamed twenty-four-year-old, Chinese-American narrator. Dissatisfied with her work and overlooked in her request for a raise, the narrator decides to leave her position as a staff writer at a prestigious tech publication in San Francisco. When her longtime boyfriend, J, is accepted into a Ph.D. program in Ithaca, New York, the narrator seizes the opportunity for a fresh start. The two embark on a cross-country move, a grand gesture of her commitment to J and a catalyst for reshaping her sense of self, but in the process, she contemplates her role in an interracial relationship.

“Captivated by the stories of her ancestors and other Asian Americans in history, she must confront a question at the core of her identity: How do you exist in a society that does not notice or understand you?” 2

Key Terms

-

Othering is a mechanism that categorizes a particular group of people based on perceived differences, such as skin color, gender, or sexual orientation, and subsequently labels that group as inferior. Othering involves zeroing in on a difference and using it as a tool to dismantle a sense of similarity or connectedness between individuals.⁴

-

The preference for relationships within the same ethnic or racial group⁵.

-

A stereotype used against members of ethnic minorities, who have historically been perceived as foreigners or outsiders in the United States, regardless of their actual citizenship or duration of residency in a particular country⁶.

A Brief History: Interracial Marriage in the United States

The history of interracial relationships for Asian Americans is complex and has evolved over time, reflecting the shift in societal attitudes and legislation in the United States. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the nation witnessed an influx of Chinese and Japanese laborers into the United States. However, as economic difficulties arose, hostility toward Asian immigrants grew, leading to restrictive legislation. Laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited Chinese laborer immigration, and the Page Act of 1875 , which prohibited the entry of Chinese women based on the assumption they were prostitutes, effectively barred entry for Asian immigrants into the United States7. Furthermore, anti-miscegenation laws throughout the country prohibited interracial marriage between Asians and individuals of other racial backgrounds.

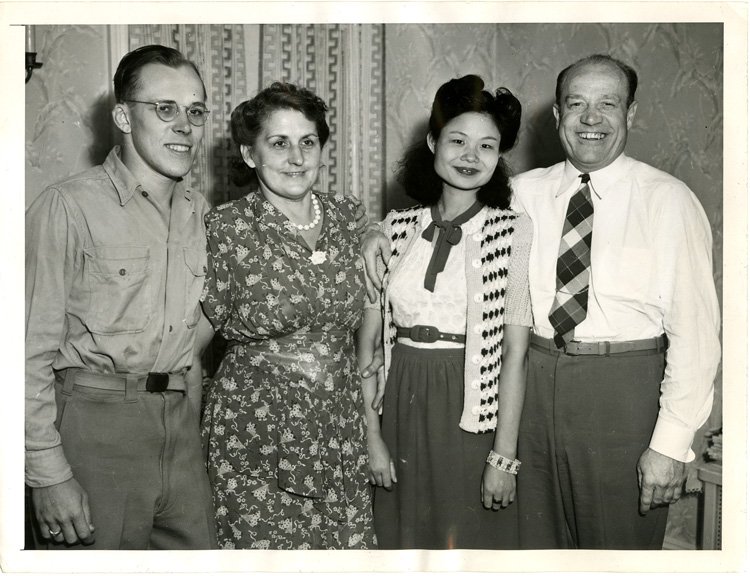

A former soldier and Chinese bride welcomed home [4]

Photograph of Mildred and Richard Loving [5]

An 1886 Anti-Chinese political cartoon depicting the Chinese Exclusion Act [3]

World War II changed the attitudes toward these restrictions. The war and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s prompted discussion about racial discrimination and equality, forcing U.S. immigration policy to change. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed and many other Asian groups gained the opportunity to become U.S. citizens.8 The 1945 War Brides Act allowed U.S. soldiers who married foreign-born women while stationed abroad to bring their wives and children to the United States. The act permitted Asian immigration despite restrictive national-origin quotas established by the Immigration Act of 1924. The war bride legislation contributed to a gradual shift in societal and legal attitudes toward Asian Americans and interracial relationships by challenging existing immigration restrictions and anti-miscegenation laws9. The Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case in 1967 struck down anti-miscegenation laws, allowing for people of different races to legally marry. With the United States becoming increasingly diverse, attitudes toward interracial relationships became more widely accepted. Today, Asian Americans exhibit higher intermarriage rates with White partners compared to other racial groups10.

Interracial Relationship Dynamics

This shift from restrictive immigration and anti-miscegenation laws to high intermarriage rates among Asian Americans prompts a closer examination of the racial and cultural implications of such partnerships. The legacy of racism and colonialism in the United States poses unique challenges faced by Asian Americans in interracial relationships. These challenges include navigating differences in cultural norms and communication styles and confronting stereotypes and microaggressions within the relationship.

Chow11 argues that racial homogamy is driven by the increased level of comfort and inherent sense of cultural and racial empathy. Additionally, Limpsomb and Emeka12 propose that couples of the same racial identity tend to provide better mutual support compared to interracial couples. While interracial couples still provide support for each other, they may lack the understanding and means to respond in ways that are validating and affirming. Additionally, it was found that White partners will attempt to support their partners but may become defensive during the subsequent discussion around race. These theories highlight how cultural differences in interracial relationships can be overwhelming for marginalized individuals. The novel illustrates this as the narrator consistently attempts to engage in racial discussions, to which her white partner, J, hesitates to respond. This reluctance to engage in discussion about race reflects the discomfort that some White partners may feel in such conversations.

“Your mother wouldn't approve of how my mother raised me. But I do, I think I do. And you're an all-American boy. I guess I couldn't help trying to be your best American girl.” - Your Best American Girl, Mitski

Racial homogamy and the inherent disconnect within interracial relationships is observed in other contemporary media as well. “Your Best American Girl” by Mitski, a Japanese-American singer-songwriter, is a love-song that explores the challenges of a relationship hindered by cultural differences. The narrative revolves around the theme of changing oneself to gain love and acceptance, vividly depicted in the music video where Mitski pines for a conventionally attractive white man who chooses another woman.

Similarly another song by Mitski, “Strawberry Blond”, delves into the narrator's love and yearning for a white man, acknowledging the impossibility of being together due to their differing backgrounds. These two songs collectively portray Mitski's experiences as a woman of color grappling with whiteness, American culture, and her identity. This resonates with the novel's narrator, who understands that her interracial relationship cannot escape the influence of race, contributing to her othering as racial differences strain their sense of connectedness.

“There’s this myth that we’re beyond talking about race in relationships. Like, Is this so normal now that we’ve somehow overcome race and racism?… Just because it’s becoming normalized doesn’t mean that we’re all good, that racism has been fixed.” - Alexandra Chang for BOMB Magazine

Your Best American Girl Music Video [6]

7

Strawberry Blond Audio [7]

In an interview with BOMB13 magazine, Chang discusses her novel's exploration of interracial relationships in the context of their normalization in contemporary society. She emphasizes that despite their normalization, racism persists, and some of these relationships may even be a product of the historical legacies of racism and colonialism. This echoes Mitski's messages about inherent racial differences and challenges the myth of a colorblind approach to discussing race in relationships.

Chang’s narrator and Mitski’s music collectively underscore how the historical legacies of racism in the United States have left a lasting impact on the dynamics of interracial relationships.

[8]

“When we talked about race, we did so mostly from a distance or as a joke, like something that could not touch the depths of this combined entity that was ‘us’. But I know we do not and cannot exist outside of it. I know I am guilty of avoiding, or not completing, the conversation. That might still be our problem.” - Days of Distraction, Alexandra Chang

Othering within Relationships

The unique challenges associated with interracial relationships may contribute to the marginalization of Asian Americans through a mechanism known as "othering." Historically, Asian women have been subjected to stereotypes portraying them as “exotic” and “oriental,” perpetuating the image of a submissive, obedient, and passive "oriental woman.”14

Presently, Asian American women face harassment and violence. The MRAsians movement15, an online Asian American men’s movement, glorifies this violence by viewing the objectification of women as something positive, associating the objectification with proximity to whiteness and a higher social position. However, this viewpoint overlooks the mistreatment Asian women may endure, contributing to their othering. Within interracial relationships, these stereotypes can be reinforced or objectified, reducing Asian partners to embodiments of these preconceived notions rather than individuals. This objectification fuels the process of othering, where Asian partners are diminished to their racial background. The possibility of objectification and “othering” is a concern that the narrator in the novel grapples with when she initially enters her relationship with J.

“It’s not that I didn’t think of our races when we first got together… Of course, I did and have. At first, they were ghostly thoughts. Really, he wants me? How could this be? Why not her or her or her? Or is it because I’m—so ghostly was that thought it could not be completed.” - Days of Distraction, Alexandra Chang

Scenes from To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before [10]

Scenes from The Summer I Turned Pretty [9]

Such histories have heavily influenced popular culture, portraying Asian American women as submissive, hypersexualized, and lacking agency, thereby reinforcing their marginalization in the media. While there has been progress in the representation of Asian American women and interracial relationships in mainstream media, as seen in works like ‘'To All the Boys I've Loved Before' and 'The Summer I Turned Pretty,' criticisms arise regarding the quality and authenticity of these portrayals. Female characters in these romances are often one-dimensional, their storylines centered around resolving feelings for a white romantic lead16. This aligns Chang’s argument that normalization does not equate to overcoming race and racism and reflect the narrator's discomfort in becoming a trailing wife, someone who follows their partner to another location because of a work assignment.

“ It’s an attempt for her to develop a lineage, to develop a sense of her identity through studying these historical figures who may or may not have had a direct influence on who she is today. As she becomes more isolated in her life, she grows increasingly obsessed with seeking answers in her research and especially through people with whom she identifies some connection.” - Alexandra Chang for The Margins

Chang further explains in another interview with The Margins17 the narrator's fascination with researching early Chinese American women and the history of interracial relationships. The narrator seeks to construct a lineage, studying historical figures to understand her identity. In this quest, she grapples with a sense of loss, relating to the broader theme of interracial casting in Hollywood, where outside figures become a source of answers for the narrator's personal relationship and identity journey.

Moreover, the heightened awareness of one's racial identity can depend on the specific context or environment in which individuals find themselves. In more diverse and inclusive communities, individuals may feel less self-conscious about their racial identity. Conversely, in environments where they constitute the racial minority, individuals can become more acutely aware of their racial identity.

An example of heightened awareness can be seen during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic when there was a surge in anti-Asian racism and the perception of Asians as “perpetual foreigners.”18 Similarly, Chou et al.19 found that in racialized environments, like predominantly white elite universities, Asian American students experienced a double consciousness. Beyond the individual level, a study20 revealed that for many interracial couples, race only becomes relevant when they are reminded of it in public situations. Such experiences underscore the hyper awareness and anxiety endured by Asian Americans in their daily lives given a racialized space or time, contributing to a border understanding of othering in society.

A Stop Asian Hate rally in Detroit on March 27, part of a nationwide protest against hate crimes directed at Asian Americans [11]

Conclusion

"Days of Distraction" offers valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of interracial relationships and their potential to contribute to the marginalization of Asian Americans. Through the narrator's experiences, the novel illustrates how interracial relationships unfold within the context of a history marked by anti-Asian sentiment. Chang's work raises thought-provoking questions about interracial relationships, Asian American identity, and history, providing a voice to questions that many young adults may find challenging to articulate.

References

Lemi, D. and Kposowa, A. (2017). ARE ASIAN AMERICANS WHO HAVE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS POLITICALLY DISTINCT? Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 14(2), 557-575. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X18000024.

“Days of Distraction.” Alexandra Chang. https://www.alexandrachang.com/days-of-distraction.

ibid

Curle, C. (2020). Us vs. Them: The process of othering. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. https://humanrights.ca/story/us-vs-them-process-othering.

Chow, S. (2000). The Significance of Race in the Private Sphere: Asian Americans and Spousal Preferences. Sociological Inquiry, 70: 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2000.tb00893.x.

Huynh Q. et al. (2011). Perpetual Foreigner in One's Own Land: Potential Implications for Identity and Psychological Adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(2):133-162. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133. PMID: 21572896; PMCID: PMC3092701.

Kilty, K. M. (2002). Race, Immigration, and Public Policy: The Case of Asian Americans. Journal of Poverty, 6:4, 23-41, https://doi.org/10.1300/J134v06n04_03.

ibid

Jordan, C. (2021). Tracing War Bride Legislation and the Racial Construction of Asian Immigrants. Asian American Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.5070/RJ41153734.

Lemi (n 1)

Chow (n 5)

Lipscomb, A. and Emeka, M. (2020). You Don’t Get It Babe: Intimate Partner Support Coupled with Racialized Discrimination among Intra-Racial and Inter-Racial Couples. Psychology, 11, 1813-1825. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2020.1112114

Lucia, Kyle W. (2020). “State of Reflection: Alexandra Chang Interviewed by Kyle Lucia Wu.” BOMB. Retrieved from https://bombmagazine.org/articles/alexandra-chang-interviewed/.

Uchida, A. (1998). The Orientalization of Asian women in America. Women's Studies International Forum, 21(2), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5395(98)00004-1

Liu, A. (2021). MRAsians: A Convergence between Asian American Hypermasculine Ethnonationalism and the Manosphere. Journal of Asian American Studies 24(1), 93-112. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2021.0012.

Chen, Eileen. (2022). “Interracial casting in Hollywood isn’t as progressive as we think it is.” The Georgetown Voice. Retrieved from https://georgetownvoice.com/2022/10/24/interracial-casting-in-hollywood-isnt-as-progressive-as-we-think-it-is/.

Prior, Michael. (2020). “The Silence Between Our Words: An Interview with Alexandra Chang.” Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Retrieved from https://aaww.org/the-silence-between-our-words-alexandra-chang/.

Huynh et al. (n 6)

Chou, R., Lee, K., & Ho, S. (2015). Love Is (Color)blind: Asian Americans and White Institutional Space at the Elite University. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(2), 302-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/233264921455312.

Kyle D. K. (2012). Resisting and complying with homogamy: Interracial couples’ narratives about partner differences. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 25:2, 125-135, https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2012.680692.

Media Credits

Artists unknown via https://www.alexandrachang.com/days-of-distraction

Photo by Alexandra Chang via Twitter https://x.com/alexandra_chang/status/1234184926574059523?s=20

Drawing by The George Dee Magic Washing Machine Company via https://reimaginingmigration.org/the-chinese-exclusion-act-resources/.

Photo by Roy Delbyck for the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection via https://www.mocanyc.org/collections/stories/chinese-war-brides/.

Photo by Francis Miller for LIFE Magazine via https://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1996028,00.html.

Mitski. (2016, April 13). Your Best American Girl (Official Video). Retrieved from https://youtu.be/u_hDHm9MD0I?si=tcS01wdBjgRt80w2.

Mitski. (2022, July 18). Strawberry Blond. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/2BTVsWPx84U?si=WbuHZ7VfHvtgubaO.

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before. (2018). Netflix.

The Summer I Turned Pretty. (2022). Amazon Prime.

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before (n 9)

Photo by Seth Herald via https://www.vox.com/2021/6/15/22480152/hate-crime-law-congress-prevent-anti-asian-hate-crimes.